Coaxing secrets from drifting art

Made-for-export oil paintings offer a rare snapshot of a lost world, revealing forgotten Qing-era wars and reclaiming a historical narrative through overlooked artistry, Zhao Huanxin reports from Washington.

Years later, Kuang spotted what he called "Haizhu II" on a California gallery website. He negotiated for five years until the work came within his price range.

When it arrived, he found an old handwritten note affixed to the back — a detail the seller never mentioned.

The note stated the painting had been purchased in 1845 by William Roache, who served aboard a 74-gun warship.

It is a piece of evidence preserved by the family of a British marine that reclaims a moment of fierce and effective Chinese resistance.

The note provides a dramatic eyewitness account unknown for at least one and a half centuries: Lord John Churchill, the commander, was killed by fire from a Chinese fort while speaking with Roache at a gunport.

This stands in stark contrast to official British records, which claimed the commander died of a long illness and was buried in Macao.

"Only after it arrived did I realize the note was even more important," says Kuang.

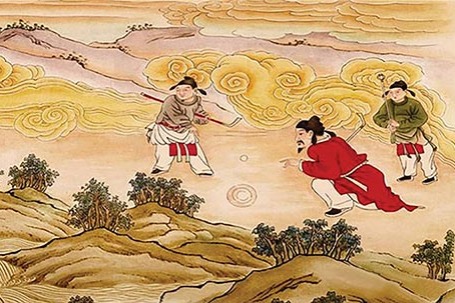

"When I saw the note, I felt the soldiers of that time deserved recognition and reward, because it might have been an important victory, but history left no record of it."

Kuang says he believes the British likely hid the truth to avoid damaging the morale of an expeditionary force already facing supply shortages far from home.

"When people talk about coastal defense, it's true that Qing forts and warships were technologically weak. But that does not mean they had no effect. If soldiers had today's defense conditions, many wouldn't have died. Yet, under those conditions, they still resisted invasion, and may have won certain battles," he says.